The pairing of Kevin Parks and Vanessa Rossetto may, at first, seem odd. Parks seems largely interested in pure portrayals of improvisation—his collaborations with Joe Foster and Alice Hui-Sheng Chang are comprised of untouched recordings and his live performances don't show signs of prior preparation. Rossetto, on the other hand, would primarily consider herself a composer. And since the release of Dogs in English Porcelain, her records have been the result of meticulous assemblage. What makes Severe Liberties so satisfying, then, is how these two elements—composition and improvisation—come together so harmoniously.

As Matthew Revert noted in Surround, Rossetto's music is interesting because her "source material is often gathered from improvised experimentation" but "is made to exist within a compositional framework." On her solo releases, field recordings are frequently juxtaposed with instrumentation or one another. This consequent reframing highlights, or perhaps imbues, certain emotional qualities to the sounds we hear. Furthermore, the musical qualities of these sounds are explored, and there's a spirit of randomness to them, even if they're coming from pre-programmed machines like those in "348315" and "Whole Stories".

Parks, then, seems like a perfect counterpart to Rossetto because of how talented he is as an improviser. Acts Have Consequences, for example, sounds like a carefully coordinated record. There's a precise balance in dynamics between both Parks and Foster and it's surprising that each track is completely improvised and unedited. That Acts Have Consequences sounds just as thoughtfully constructed as Parks' record with Hong Chulki and Jin Sangtae, an album that was mixed and edited, only further attests to his abilities.

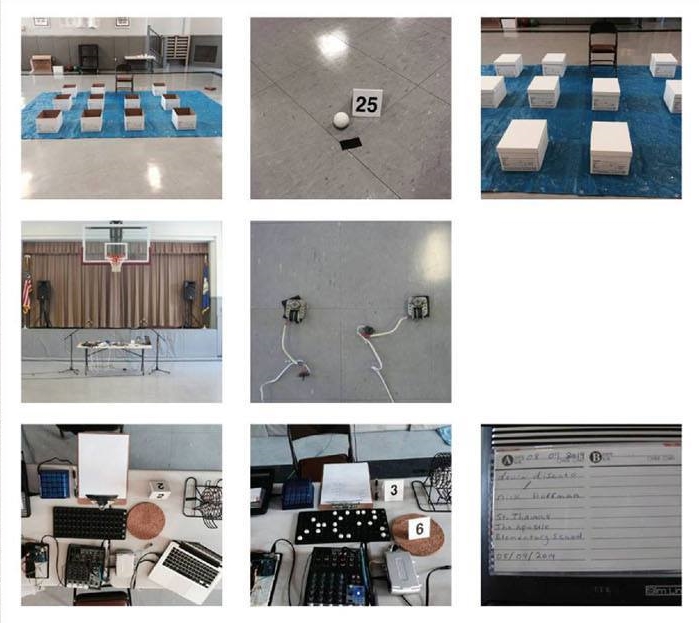

The combination of these two artists leaves us with Severe Liberties, an album whose title refers to the numerous edits that were made with the source material—hours of improvised recordings taken in Vanessa's home. And as the record starts, it makes that idea known to the listener with the sound of contact microphone-derived sounds bouncing across both channels. As Revert's fantastic cover art portrays, Severe Liberties is a record about exploring domestic spaces. It's about our homes and the familiarity of it both as a place and a feeling. And with three tracks that range between 14 and 22 minutes, we're able to get a feel for this space. As is characteristic of previous albums from both Parks and Rossetto, these long-form pieces allow for an involved engagement with these tracks and get a sense of their unfolding narratives.

There are a lot of sounds we hear across these 53 minutes—zippers, the stacking of dishware, processed electronics that sound like fireworks—but it's all so purposefully considered. Take "the details of the anecdote": early in the track, Vanessa walks around and we hear floorboards and doors creak. She eventually turns on a faucet and water begins to funnel down the drain. A high-pitched tone then appears, and because it's so noticeable, it naturally draws our ears back to the running water. And in that moment, we're able to compare both sounds and acknowledge and appreciate the inconsistent rhythm of the water's movement. A softer electronic hum soon appears underneath to assuage the previous tone and the piece moves forward. This sort of methodology permeates Severe Liberties and is exactly what makes it so captivating: there's a constant redirecting of our ears—across field recordings and instrumentation, timbres and rhythms, melody and silence—and it feels like a tour of the house, perhaps not lineally in space or time, but in mood.

Despite the variety of sounds that exist inside Severe Liberties, a few seem especially significant. One of those is the use of voices. While Rossetto has incorporated vocalizing before, and even used her own voice to provide a meta-narrative in Whole Stories, what's here seems especially candid and naturally presented. About three minutes into "seeing as little as possible", we hear her casually talking with someone who is presumably an acquaintance. It's a short exchange, and it's obfuscated by a bit of noise, but it feels all the more personal because of it. The attention isn't drawn towards the conversation. Instead, it's just another sound in the mix, another element that brings up a familiarity of home—the short but polite conversations we have with neighbors. And at the end of "they sit", we hear Rossetto ask Parks, "are you getting tired?" It's humorously positioned, as Parks gets cut off and the following track abruptly starts, but it also provides a glimmer of humanness to the piece. It's safe to say that the human voice would provide such a feeling regardless of what it said, but it's also the genuineness of the question here, and the sound of a weary Parks replying "yea" that makes it so effective. Home is, after all, our place of rest and where we should feel cared for.

Even more emotional is Kevin Parks' guitar. It's often used here alongside contact microphones to create different textures but what really stands out is Parks' decision to incorporate highly melodic instrumentation. These passages appear about halfway through each track and when they arrive, dominate the mood of the piece entirely; it's a sharp contrast with how all the rest of the sounds on the album function. And consequently, it's why these sparse guitar chords and melodies feel more potent than when they appeared on Acts Have Consequences. Nevertheless, Parks' guitar feels wholly appropriate, essentially contributing to the nostalgic atmosphere and tone that the album often evokes.

Perhaps the most interesting element on Severe Liberties, though, is silence. There are four extended periods in which we hear absolutely nothing and they each function in multiple ways. For one, they provide a nice flow to the album; their presence is a building of momentum through repose. At the same time, their placement in each track also allows for the sounds that precede and follow them to be all the more effective. Most compelling, however, is how they allow for us as listeners to fill in the space with the sounds of our own home. It becomes a participatory event, which naturally makes the record all the more intimate.

There are numerous reasons as to why this record is such an accomplishment but it ultimately comes down to how beautifully these artists' styles converge. They're both incredibly talented, of course, but the natural merging of styles on Severe Liberties goes beyond that; it's because both Parks and Rossetto were willing to accommodate their own ideas for a greater whole. Various aspects of Severe Liberties sound characteristically Parks or Rossetto-esque but the final product is something unlike anything in either artists' discographies. And for that reason alone, Severe Liberties is worth hearing. Fortunately, it's a success in many other ways as well.